Women were equal partners in the founding of Berea College community. Shoulder to shoulder with their husbands, Matilda Fee and Elizabeth Rogers were integral players in the challenging drama of Berea’s earliest years.

Establishing any community in an untamed wilderness that had to be cleared of dense thickets was a notable accomplishment, one that required perseverance and lots of hard work. Yet, an even greater accomplishment was establishing a community here based on the equality of all people. In Kentucky during the pre-Civil War era, mainstream society considered it radical – almost unimaginable – to acknowledge blacks and whites, and women and men, as social equals.

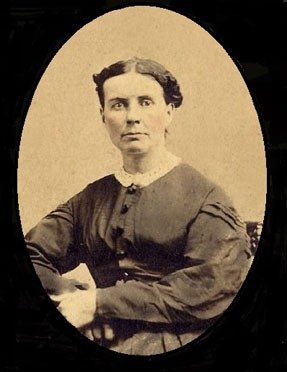

Matilda Fee

Matilda and John Fee were fiercely intent on organizing a church and school for “all people …” from all “nations and climes” on the Berea ridge. In spite of initial support from Cassius Clay, they found resistance was rampant beyond the ridge. Pro-slavery factions called Berea “a menace to Kentucky’s best interests” and “a stench in the nostrils of all true Kentuckians.” Mobs repeatedly threatened violence. Matilda Fee saw her husband beaten severely on numerous occasions and tended his wounds.

In describing Matilda’s qualities, John Fee said he found in her “that affection, sympathy, courage, cheer, activity, frugality and endurance, which few could have combined, and which greatly sustained me in the dark and trying hours that attended most of our pathway.”

Elizabeth Rogers came with her husband, John A. R. Rogers, to help the Fees in their work and she was Berea’s first female teacher. In her memoirs to her children, Elizabeth Rogers tells of their arrival on the Berea ridge. “It was a rainy, March day, your father and I made our entrance into Berea. We stood on the hill, looking across through the trees at the little slab schoolhouse that was to be the beginning of Berea College. The unpainted schoolhouse with its broken windows hardly seemed a worthy field for my aesthetic, scholarly husband, but he saw the work with prophetic eye . . . and only nerved him to more constant toil. On that drizzly afternoon, it needed a prophet’s eye to see in the most distant future, even a ray of hope. My vision was clouded, and the wet, drooping branches accorded with my spirit, and my heart was heavy. Once in the harness however, I never looked back, and entered upon the work with a zeal and enthusiasm second only to your father’s, and our work grew like magic.”

Elizabeth Rogers

At the time, Berea was a sparsely inhabited wilderness where the fledgling school opened in the old district schoolhouse, a one-room clapboard building. The school was like a seed planted in fertile soil, eventually becoming a college that would “educate not merely in a knowledge of the sciences, so called, but also in the principles of love in religion, and liberty and justice in government.” Thus learning, informed by the gospel, would make the nascent Berea College a school for reform.

Such reform is not always welcomed. Vigilantism continued in the region until Christmas Eve, 1859, when mobs drove the Fee and Rogers families and their fellow workers from the state. Forced to leave all personal possessions behind, their exodus from Berea took place in the midst of a blinding snowstorm. Tragically, Tappan – John and Matilda’s youngest son – died from diphtheria after exposure to the cold.

Facing such hardships, more timid individuals may have allowed Berea’s utopian experiment – unique to the whole American experience – to exist only as a footnote in the annals of history were it not for the fact that before the end of the Civil War, the exiles returned to resume their “never relinquished work.” Such a spirit of strong determination and deep commitment continues to inspire women and men. In her memoirs, Elizabeth Rogers said, “That first school was to be a feeler. The people from the mountains and from near plantations flocked to the school doors asking for admittance. All that we could possibly do was done to create a feeling in favor of the school, and we succeeded better than we had even hoped. . . . Carried on by an enthusiasm which our pupils shared, we laid broad and sound the foundation of hard study and the beginnings of Berea College, though so small, were all in the right direction.”