Much like her alma mater, Berea College alumna and award-winning novelist Alix E. Harrow ‘09 is no stranger to making history.

Harrow was already in rare company when she joined Berea College at age 16, and she made quick, studious work of her history degree by graduating in only three years. Since then, Harrow met the love of her life, earned her master’s degree in history, won a stack of awards for her luminous short fiction, signed her first book deal, created two wonderful children, and returned to Berea so her husband, Nick Stiner ’15, could earn his own Berea College degree in music.

In 2019—just ten years after claiming her degree—Harrow won a prestigious Hugo Award for Best Short Story for A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies. Then Harrow outdid herself the very next year by becoming the youngest woman in the history of the Hugo Awards to be nominated for Best Novel for her debut, The Ten Thousand Doors of January.

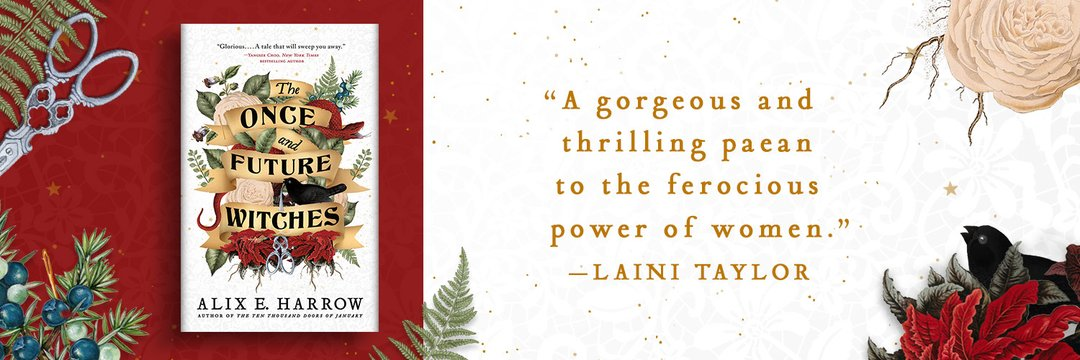

Luckily for us, Harrow agreed to speak with us on the eve of the October 13th release of her second novel, The Once and Future Witches. Read on for our full interview with Alix Harrow about how it feels to write award-winning historical fiction while making history herself.

Author Interview with Alix Harrow ’09

1.) What was your history with fiction writing before coming to Berea College, and what writing did you most enjoy while you were a student of Berea College?

This is where I should talk about my lifelong dedication to the art and craft of fiction, but the truth is that my only writing experience was playing the MS DOS game “Storybook Weaver” as a kid and writing a novel-length Tamora Pierce rip-off in middle school. By the time I got to Berea I was determined to pass as a serious adult who had put away such childish habits.

But as it turns out academic writing and fiction aren’t that dissimilar. Both are arguments about reality, narratives assembled from found objects. Both of them benefit more from clarity than cleverness, and both of them will leave you facedown in a library carrel, considering changing your name and fleeing into the hills rather than writing another sentence. I am grateful in particular to Dr. Rebecca Bates and Dr. Robert Foster, whose classes most often landed me facedown in the library, to my great benefit.

2.) Please tell us your artistic and career paths after graduating from Berea, especially how you created such fantastic short fiction and landed a deal on your first two novels.

I am flattered by the suggestion that I have a career, or a path leading to it! I graduated from Berea at 19 at the very beginning of the Great Recession.…If I stumbled into a career, it was only by accident, in the dark, by dint of luck and privilege. Before I wrote a single story, I was a blueberry raker, a research assistant, a cashier, a grad student, a TA, a housekeeper, an instructional designer, and an adjunct.

In my last semester of grad school, I got anxious and sad, the way you do in your last semester of grad school, so I checked Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea books out from the library, which I hadn’t read since I was a kid. And they woke me up, gave me back a sense of wonder and whimsy. If my life was an old Disney movie, that would have been the moment the film switched from black and white to technicolor.

After that I started experimenting with writing and submitting short stories, and after that I got unforgivably lucky. One of my stories came out in Apex Magazine and got passed around a little on Twitter; an editor at Orbit Books messaged to ask if I happened to have a novel. I asked for a week to polish it, sent it off, and signed an agent and a two-book deal within about a month.

3.) Like the literal witchcraft practiced by historical suffragettes in your fabulous new novel, The Once and Future Witches, your unique pairing of history and fantasy creates a fascinating tension between objective and imagined pasts. What roles do you think imagination and fiction play in writing history, and how did your time at Berea College influence this outlook?

It is my extremely biased opinion that every novel is historical. Every book is a period piece, an artifact of the moment it was made and a commentary on everything that came before it. So calling something historical fiction is just a way of indicating to the general public that the characters might wear corsets.

More seriously, my feelings about history and imagination have [laughs] changed over time. I used to feel a certain obligation to the truth; I thought the worth of fictional history could be measured by how closely it adhered to actual history. But I’ve come to embrace the freedom of speculative fiction—to exaggerate, extrapolate, ignore, and improve the truth. You know that Twain quote, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes?” I want to make my fiction rhyme with history, rather than repeat it.

4.) Since a degree doesn’t guarantee a living-wage job in any field, in what ways did Berea’s Tuition Promise Scholarship influence your post-grad decision-making and freedom thereof?

I don’t think I understood the privilege of graduating without debt until I left the Berea Bubble and met other fresh-out-of-college kids. Some of them were like me, in that they were young and aimless and picked their majors based on how cool the classes sounded in the catalog, but none of them were really like me, because they had debt.…I wonder sometimes how many books and plays and oil paintings and really good albums we won’t see or hear, because we’ve sunk an entire generation into debt in an economy that won’t reward them for it.

5.) How did you learn how to write such cohesive and compelling novels, and what were some of your biggest challenges to getting published?

I learned to write by reading, like everybody, and I’m not sure I’ve faced any particular challenges in getting published beyond the fact that publishing is, in itself, challenging. It sits at the uncomfortable intersection of capitalism and art, which makes it hyper-competitive, unfair, baffling, sometimes mercenary, and always emotional. I started out getting lots of rejections, followed by a very few acceptances, followed by the bittersweet privilege of one-star reviews on Goodreads. The story that won the Hugo was rejected from every professional market except one; I rewrote my second book from scratch after receiving an 11-page edit letter on an early draft. But ultimately, I’m white, able-bodied, and educated, which means I’ve gotten to skip many, many challenges in publishing, and reap greater rewards.

6.) You and your work deftly handle enormous themes like race, class, gender, sexuality, science, immigration, and other social forces. What is the importance of engaging with these themes, and how (if at all) has Berea College’s missions and history factored into your skillful treatment of them?

I don’t know how deftly or skillfully I’ve dealt with any of them, but those sociocultural themes all strike me as dimensions of power—and what’s more interesting than power? Who needs it and who has it and how they wield it, where they got it and what they’ll do to keep it—in a lot of ways, those are the questions that drew me to history in the first place. One of my favorite classes at Berea was a comparative study of modern empires, because I felt like I was suddenly seeing the why behind the power structures of the present day, the hateful armature beneath our everyday injustices.

And then I had Berea to make sense of my personal place in history, too. It’s easy, as a white kid from nowheresville, Kentucky, to feel like your history is ugly and small. Berea gave me a version of small-town Kentucky history that included radicalism, dissent, resistance, and justice, and it encouraged me to continue living that history.

7.) What advice would you offer aspiring writers, poets, and other artists, especially from Berea College?

I’m skeptical of giving advice, so instead I’ll mention two kinds of advice you don’t need: bootstraps and grindstones. Lots of people will tell you they achieved their artistic careers by pulling themselves up by their bootstraps and keeping their noses to the grindstones, two technologies which, not coincidentally, no longer exist. In my limited experience, the only people who talk about bootstraps are the ones who never really need them, and the only people who make art are the ones who refuse to grind themselves down.

By SAM MILLIGAN

Really great way to be introduced to this writer. Thank you.