Article Written by Charity Gilbert

As a young child, I recall the times my Mama told me to be careful not to go down to the creek. “If you can’t see the bottom, don’t go in it or you might drown.” She’d say.

Charity and her two brothers helping out in the garden when they were kids

This was in the small community of Fogertown, Kentucky. I was raised on a tobacco farm where our family had rented homes and helped to work the land. I recall the rain. Almost every time it rained, the bridge leading out of our holler would flood, and we’d get to miss school for the day. We’d go down to the edge of where the muddy water had spread itself out across the “bottom”, as we called it. I recall seeing that muddy, cloudy water after the rain. Mother warned us not to touch that water, as we didn’t know what was in it. We often took pictures of the flooding, as we were trapped. We lived up high, though, and the water would never reach us.

Photograph of Charity’s Granny and Papaw Gilbert

In my teenage years, we moved to Oneida, Kentucky, to be closer to my granny. It was an adjustment, but I felt more at home in Oneida than I ever had. The connection I felt to that land and the people there was something I still can’t explain. And at our new home, it didn’t flood. There was a small creek that ran all the way down the holler. I recall a rock I would sit on, up in the holler. I’d put my feet down in the water and pull out my guitar. That was my spot. I wrote many of my favorite songs there, sitting by the creek.

I came to Berea to go to college, and stayed to work this summer. I recall when the flooding happened. I was scrolling on Facebook when I saw photos of the water in Whitesburg. Appalshop was halfway underwater. The pit in my stomach was something I hadn’t felt very often in my life. I first thought of all the history that was probably lost. Then came the concern for  the people who were affected. And I suddenly wondered how Oneida was. I call my parents every day, and for the previous day, I hadn’t been able to. I thought it was fine though, since, years prior, we had a pet who chewed into our telephone line a bit. Now, when it rains, the water gets in the lines and I can’t call home for a few days. I assumed that was the case. But then I realized no one in Oneida had made any posts on Facebook or online for the last day or so, which concerned me. I made a post asking friends if they knew how things were in Oneida. I expected flooding there but not specifically on Bullskin, where my family lives. I looked at the post a few hours later to find comments.

the people who were affected. And I suddenly wondered how Oneida was. I call my parents every day, and for the previous day, I hadn’t been able to. I thought it was fine though, since, years prior, we had a pet who chewed into our telephone line a bit. Now, when it rains, the water gets in the lines and I can’t call home for a few days. I assumed that was the case. But then I realized no one in Oneida had made any posts on Facebook or online for the last day or so, which concerned me. I made a post asking friends if they knew how things were in Oneida. I expected flooding there but not specifically on Bullskin, where my family lives. I looked at the post a few hours later to find comments.

One read: “Last I heard it was flooded on Bullskin pretty bad. Granny’s yard is gone. They closed down Bullskin right at Panco.” (Panco is the church I go to when I’m back home.)

It was a few more days before I could call home again, but I was so glad to hear from my family. They were doing well, aside from having lost a refrigerator full of food due to not having electricity to keep it good. It took a full month for their gas to get fixed, so they were cooking on a little electric hot plate all the way up until the last week of August. The gas meter had been pulled from the ground as an impact of the flooding. The thing about this flood wasn’t the depth, it was the speed at which it came down. It came in the night and hit so hard and fast that the water just rushed out of the hollers into the lowest place it could go, bringing down trees and pieces of the hills with it. The lowest place for it to go around my home was the holler across from ours. Our road was up higher, but the one across from ours went down into a field and then back into the holler. My dad had a friend who lived in a small house/shack there. The man came up to our house and told him that he woke up surrounded by water. He had to bust the window to escape and worried about his dog, but thankfully found it. The little house is no longer standing there.

but the one across from ours went down into a field and then back into the holler. My dad had a friend who lived in a small house/shack there. The man came up to our house and told him that he woke up surrounded by water. He had to bust the window to escape and worried about his dog, but thankfully found it. The little house is no longer standing there.

An older man who lived back in that holler sadly passed away due to the flooding and another person passed in Oneida as well. The roads had completely caved inward in a few places. And it was soon apparent that while our community had been hit hard, many others had it worse. Thinking about that destruction and loss was devastating.

A week later, I was able to visit home. The mudslides that had taken trees and bits of the hills left me shocked, but it was clear that I had missed the worst of it. My Granny’s creek had rerouted, and her little driveway is gone, leaving no way to get into her yard by vehicle. The creek where I wrote songs and watched the minnows was mostly dried up because it had widened. It must have had a blockage way up in the holler. The roads were already fixed, which blew my mind.

When I went home most recently, the first weekend of September, the spring that has been a source of clear, refreshing water had a new sign beside it. When I asked my dad about the sign, he said that the water was now contaminated with E. coli, he believes as a result of the heavy flooding. People used to stop there almost every time you’d go by it, filling up jugs of water. Now it’s contaminated and can’t be used anymore.

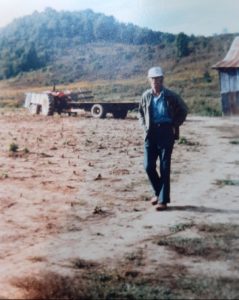

Charity’s Papaw Philpot next to the field where they’d plant tobacco when she was growing up.

There was some good from the flooding, though. That is, community. It made me think about how quickly people come to help in times of crisis. As we got to my house, I realized that for many in our community, similar situations are just a part of life. While some did lose their homes and some their lives in some of the hollers, the food disparities and the “make do” attitude was just how you lived. It is how my family has lived for all of my life. Of course, it was stressful, but the disparities already present in those areas didn’t feel much different than this. It was just a slightly different roadblock.

The outsiders who came in to help saw the poverty and the way we lived, and many thought it was a result of the flooding, but a good portion of it was just the struggle of living in such a rural area with very little opportunity and few resources. Something as simple as needing a new car part can throw off everything when you live in a poor community. These people are adaptable, tough, and generous. While I’m proud to be a part of this community of tough individuals who do what they can to make it work, I wish there was more security.

I’m thankful that people stepped up to help the community in a time of struggle. There are those in the community who do that daily. It’s in the form of the congregation at Brutus Baptist church, who, even before the flooding ever happened, would come around to the community once a week and give a meal to everyone. It’s also in the form of Jerry Rice, the preacher from Panco Community Church, who, to most outsiders and even those who know him well, seems a bit crazy. He’s someone who dreams big when it comes to the community and he will make things happen if he sets his mind to it. Members of the church are known to help out the community with yard work, housing repairs, and whatever is needed when they are able. And if you go on down the road, there is another Pastor, Brad Stevens from Church of God Worship Center, who made sure people were safe in the time of the flooding. I could also name countless individuals who have helped during this time of need in the community, but I will refrain from doing so.

As rebuilding continues, I hope we can all take note about how these communities have banded together to help each other. No matter how muddy the water, the people in Eastern Kentucky are strong, adaptable, and willing to reach out a hand to their neighbor when times are hard or when the water starts rising.